An Australian born out of the Bosnian War

By Dzenana, ASRC volunteer

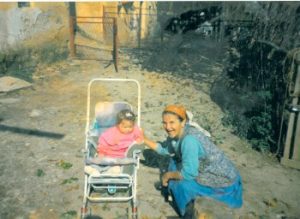

We lived in a town called Konjic, in what is now known as Bosnia and Herzegovina, nestled in the Dinaric Alps 50kms south of Sarajevo. We had Serb and Croat neighbours, but Konjic was a Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) town and at the time, it didn’t seem likely that the border skirmishes would affect us. But the Bosnian War wasn’t bound to borders and within a few months, our family found ourselves the target of an attack to cleanse our country of all Bosnians Muslims. I was only one years old.

Leaving seemed like a mad choice; where would we go? How would we get there? My mother, who was only twenty-one, had two little girls to take care and was in the middle of a divorce. We were Muslim, but not in any recognizable way. Bosnian Muslims generally aren’t. They smoke, they drink, they swear.

Some women wear hijabs, but most don’t. My mother didn’t. The line between Muslim and ‘Other’ was fuzzy and it didn’t seem possible that genocide was under way. We were too much the same.

So we moved around a lot – staying with benevolent strangers, in refugee camps, in Serbian camps, and on the streets. My mother was trained as a nurse and sometimes found work in hospitals. She was paid in slices of bread and glasses of milk which she saved for my sister and me. But it wasn’t enough and we had beg or eat whatever scraps we could find.

In the background of course, there were the gunfights and the bombings, but more pressingly, there was emptiness and pain in our bellies.

I remember playing with my little sister outside when bombs began to fall. A woman – I don’t know who – ran out to us, hooked us under each arm and ran into her apartment. I remember listening to the crash of bombs and falling debris as I sat in her kitchen, contentedly eating the inside of a banana peel I had found in her bin. There are two things that I remember vividly about that day; the grainy softness of the banana peel and the look on my mother’s face when she eventually found us. We realised then that we have to leave Bosnia.

Thousands of women and girls went missing during the war. A kind Croatian man helped us escape and drove us to the border but we couldn’t cross with him. We were Bosnian and wouldn’t get through the checkpoint, so we walked across. But the border was covered in landmines – at this point, I remember my mother pausing and looking across the field, my sister on one hip and me, standing there, my hand in hers. I wonder now, what she thought about in those few moments of hesitation. She was about to walk away from the life she had built.

We’re the only ones that made it out. Everyone else stayed – her mother, her seven siblings and their families. They have had to live with the shelled buildings, the holed walls, the landmines, broken people and the youth unemployment rate of 60% twenty years on.

Croatia was hard. We lived under different names in order to receive a tiny portion of bread. My mother cleaned houses and did the washing for other people so that she could afford to buy us something fresh to eat. Sometimes the man who took us over the border bought us some food. It wasn’t easy.

My mother applied for our humanitarian visas in secret. We chose Australia because, only because out of all our options, it had the shortest waiting list. This felt like the first real choice my mother made – everything leading up to that point was a series of slamming doors, forcing us one way or another.

We arrived in Perth in 1995 and finally found safety in government housing alongside other refugee and low income families. My mother worked three jobs and had to retrain as a nurse. We didn’t speak a word of English so school was hard for a long time. We went to a secular school but every morning the teacher lead a class prayer. I was excused from participating, but sitting at my desk, I was conscious of my unbelieving hands and would steeple them into prayer to fit in. Many people were kind to us, but some were especially cruel. My friends who were dark skinned and also refugees were teased, so I learned to be quiet.

My family didn’t fit in easily because of our funny accents and our funny food and our wide-eyed staring.

We acted differently and sometimes it amused people. The first time we heard a car backfire, we took cover.

People laughed. But we worked hard at fitting in, shedding our accents and stepping into Aussie intonations. My family tended to avoid other Slavs and my mother worked hard to cook western food when our Australian friends came over for dinner. By high school, no one knew we weren’t Australian except for our weird names.

Twenty-one years on, I feel lucky to be Australian. This country has shaped my values, given me safety and allowed me and my family to build whole new lives. My story is like that of so many others who arrive here in search of asylum. Some people are lucky to be born Australian, others have to fight and make sacrifices for it.

#TheirStoryOurStory

————-

At some stage in our history, a family member has sacrificed something so that we, or the next generation could feel safe, loved, and to help us prosper. These stories recognise the importance of giving a person the opportunity to feel safe, and build a better life.

To directly support and empowers over 3,000 people seeking asylum each year to find safety, you can donate to our Christmas Appeal using the form below.

Leave a reply

Connect with us

Need help from the ASRC? Call 03 9326 6066 or visit us: Mon-Tue-Thur-Fri 10am -5pm. Closed on Wednesdays.